At sunset, the little soul that had come with the dawning went away, leaving heartbreak behind it. -L. M. Montgomery

The hurricane brought with it all of the expected hardships: wind, rain, flooding, downed trees, power outages. For me, it also brought a unique opportunity to look for old family photographs as I attempted to stave off the mounting cabin fever. And so it was, with the kiddo safely ensconced with his grandmother, I set out to my maternal great-grandmother’s house to raid the attic. Though I only had to run across the street, the relentless rain had me soaked in 10 seconds flat. I didn’t care; I was on a mission.

I was dead set on finding a specific box of photographs that I had not seen for some 20 years. Spurred into action by a friend’s Instagram post on the subject, I knew I had to find one photograph in particular: a 1933 photograph, hand painted in delicate blue and pale pink hues. I had no hope of knowing whether the pictures would still be there; the house had undergone a few renovations and cleanings since I last laid eyes on the dusty cardboard box which I now sought.

(warning: post contains morbid imagery after the jump)

My uncle groggily opened the door as I stood there shivering in the breeze. Apparently I had interrupted his mid-afternoon hurricane nap with my knocking. I explained to him what I was looking for and he shook his head and laughed.

“There ain’t no tellin’ what’s up there. Your mama already threw out a bunch of stuff. But sure, you can look around.”

He followed me to the attic door, swung it open for me, and murmured a sleepy “Good luck, boog. If there are pictures up there, none of us has ever seen ’em”.

I smiled and thanked him, ducking under his arm and trudging up the stairs. At one point in my childhood, I lived in this house for an 11 month span. In that time, I had rooted through every nook and cranny the old attic had to offer, including the box. My memories of the event were still vivid enough that I could recall the exact spot where I, no more than 12, had first blown the dust off of the old photo albums.

I returned to that spot, hoping it would be a cut and dry case. Alas, my uncle was not joking when he said that my mother had cleaned up shop. That whole side of the attic was now empty, save for a rack of old clothes and a mattress. My heart sank, but my determination rose in spite of it.

I climbed over bags of old clothes, crawled through tiny passages, and shimmied over boxes bedecked with dust and webs. I looked through giant tubs of dishes, screamed at (dead) spiders that fell out of trunks, and flipped through old books (enjoying the smell, of course!). After an hour and a half, I had gone through every box, bag, and trunk in sight, but no photographs. I cursed, sighed, and closed my eyes.

If they’re here, I thought, I’ll find them. I stood up and scanned the attic one last time. There was one place I was unable to reach for fear of a brown recluse. There was one little box in the farthest reaches of the attic, pushed up against the slanted rafters, making even harder to approach. I chewed my cheek and frowned. That’s the box.

Sure enough, as I leaned over to get a closer look, I saw in the sprawling handwriting of my great-grandfather the word: Photographs.

Damnit.

I was going to have to brave the recluse if I wanted to get the prize. I did a little dance to amp myself up, shaking out my legs and arms, rolling my head back and forth to stretch my neck. You’d think I was about to run a marathon, and in truth, my heart rate would probably be high enough to make that believable. Arachnophobia isn’t just a movie for me, y’all, it’s a documentary.

I grabbed one of the moth-eaten coats draped over a dusty chair and held it out in front of me like a shield (after thoroughly searching it for spiders, of course). Then, with all the speed and agility I could muster, I scrambled over the boxes and bags towards the recluse. I chucked the coat on it with a squeal of terror, lunged at the box, and dragged it out of its musty refuge and into the light of the stairwell landing. This better be the box.

I sat on the top step and flipped the old cardboard folds open. There were definitely photographs – hundreds of them. My breath caught in my throat as I pored over each one. There were baby pictures of my Papa, tugging at my heart strings. Pictures too, of his sister, and my great-grandparents, and of relatives unknown. Pictures from their youth, which I had never seen. Even if this wasn’t the box, I was grateful for what I had found. Old newspaper articles about the family and letters from relatives were peppered throughout the pictures, and I knew this would be a wonderful learning opportunity about my own family.

Down amongst the old photographs, news clippings, and letters, I spied a flash of pale blue. I set aside the clump of photos on top of it and pulled it up from the bottom of the box. There it was. There he was. A little baby, swaddled in silk with blue eyes, holding a pale pink rose.

The first time I held this picture at the age of 12, I knew what it was, but not what it meant. I had no idea there was a name for that sort of thing, other than creepy, and I certainly didn’t understand why anyone would take, let alone keep, a photograph like this. Of course, now I know and understand completely.

Memento mori photography arose out of the Victorian era, where death was ever-present in day to day life. As photography was a new, rare, and expensive technology, often the only picture of a person to be taken was at the time of their death. These photographs were celebrated, and account for an enormous proportion of all photographs taken in the mid-to-late 1800s.

Given the long exposure times for early cameras, the dead were seen as the perfect models for the craft. Indeed, in looking at memento mori photographs of families, it is not uncommon to find that the deceased person is in much sharper detail to the live ones, who appear blurred from breathing and other natural micro-movements associated with this thing we call living.

The practice was at its peak in the late 1800s through the early 1900s. With the advent of more afforable photography methods, and the increase in lifespan thanks to the discovery of antibiotics such as penicillin, memento mori photography began to wane in popularity. Still, however, the practice was seen well into the 1940s in America and abroad.

Such is the case of my great-uncle, Gary Lee. He died at the age of 8 months in 1933. As a lower income family in a rural area, there had not been time to have a living photograph taken of the child before his untimely death. My great-grandfather requested these memento mori shots that I now share with you. In very faded notes on the back of the black and white shot, the photographer had written down the instructions on how my great-grandfather had requested the photographs be painted.

Little Gary is shown here with his eyes open. To the untrained eye, it would be easy to think that this is merely a living child in repose. However, it was not uncommon in memento mori photography for the eyes to be propped open, or painted on later in an attempt to bring a hint of life to a dead loved one. With Gary, he has had his eyes washed over in blue, with pale pink tones adding a life-like blush to his cheeks, and a bit of color to the rose in his hand. While color photography did exist in this time period, it was an expensive and not yet streamlined process. In cases like these photographs, artists would hand paint, utilizing watercolors, acrylics, or pastels, to achieve a colored effect.

Here we see little Gary Lee reclined on a pillow, rose in hand as above. This is the photograph that has notes on the back regarding the coloration of the other shots. In this picture, Gary is reclined on a pillow. In some memento mori, the mother, or another family member, can be seen holding the child in a loving embrace. Occasionally the mother may be hidden beneath a blanket to make the child appear as if they are sitting up on their own.

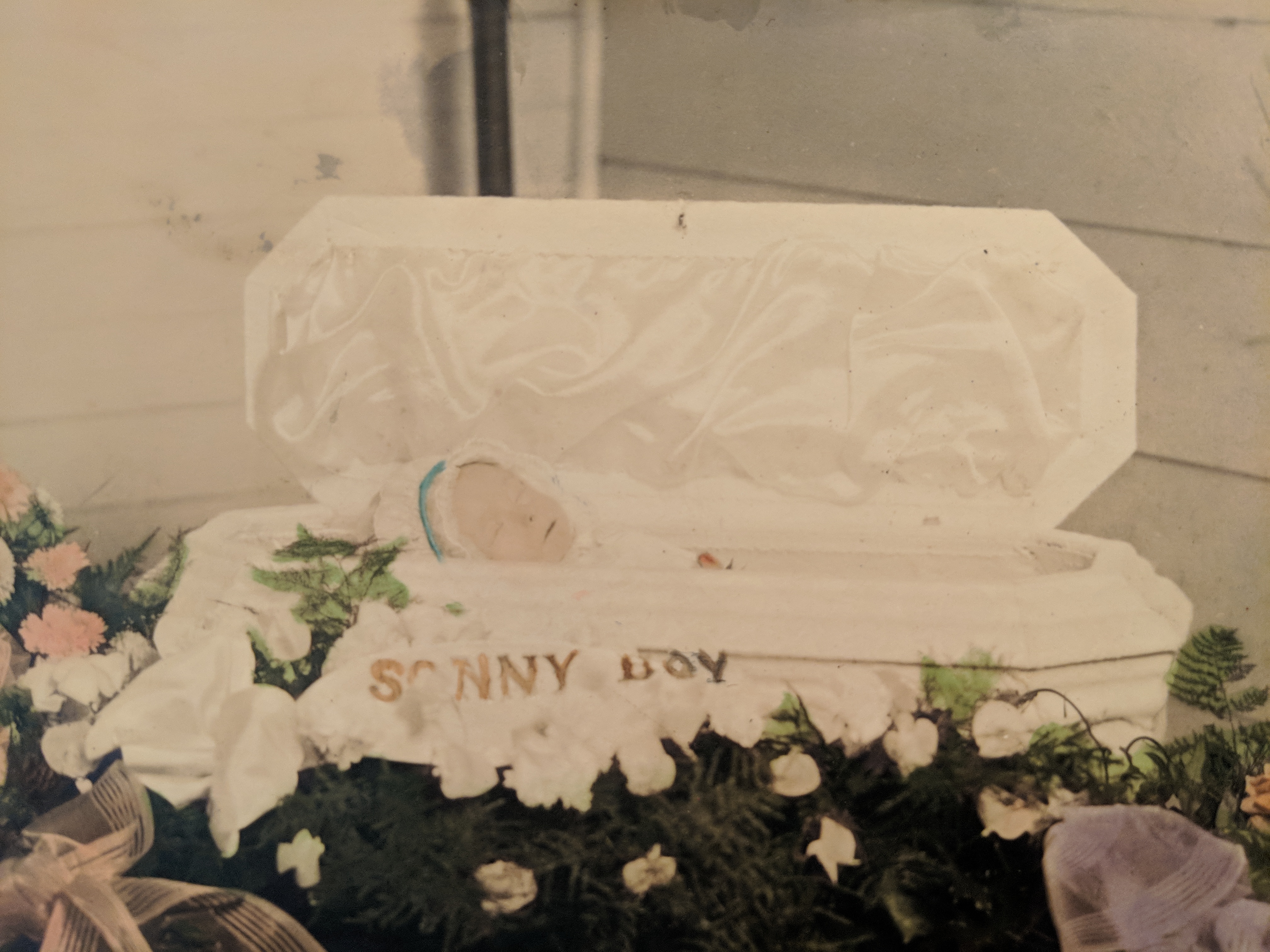

Finally, a picture of Gary in his coffin, surrounded by flowers and silk. The burial of a child was something that many families saved for from the birth of their first. Whereas we now have college funds, car funds, or rainy day funds, a funeral fund was of the utmost importance in the days where life could be snuffed out in an instant.

These are the only three remaining photographs of Gary Lee. In fact, they may be the only ones at all, as having copies made of photographs in that era were extremely expensive. I am grateful to be able to share his pictures with you, and to let his name be seen and spoken again. Though his life was short and tragic, I will never forget him.

I learned much about my great-grandparents, their lives, Gary, and much more while sitting on those dusty stairs as the rain pattered on the old, worn out shingles above. I plan on telling you all about their story in an update coming soon. There are some family secrets which remain hidden forever, and then there are some just waiting to be found, guarded by a brown recluse.

Best wishes and sweet dreams,

-Megan

Leave a comment